“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

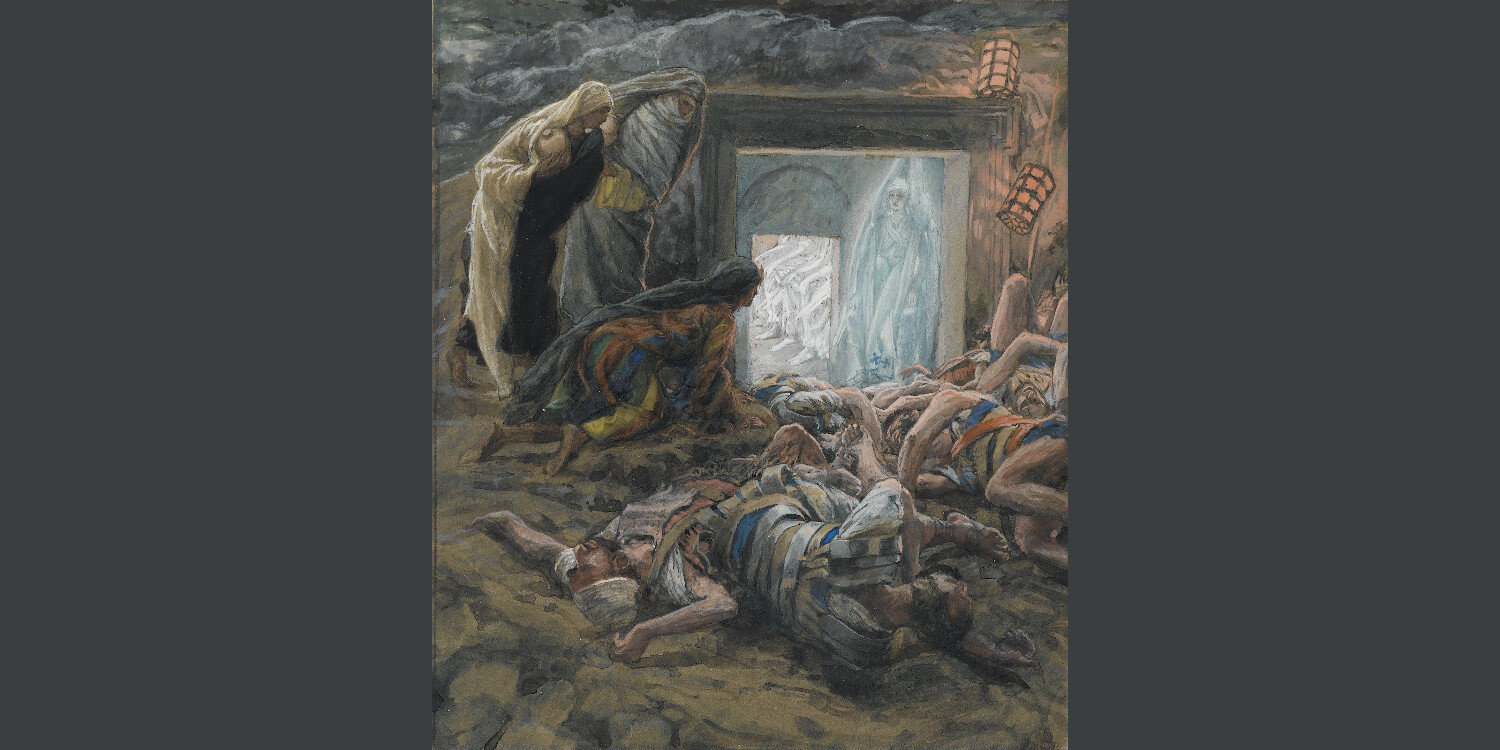

Mary Magdalene: Faith, Courage, and an Empty Tomb

History unjustly sullied her name without evidence, but Mary Magdalene emerges from the Gospel a faithful, courageous and noble woman, an apostle to the Apostles.

History unjustly sullied her name without evidence, but Mary Magdalene emerges from the Gospel a faithful, courageous and noble woman, an apostle to the Apostles.

As an imprisoned priest, a communal celebration of the Easter Triduum is not available to me. My celebration of this week is for the most part limited to a private reading of the Roman Missal. Still, over the five-plus years that I have been writing for These Stone Walls, I have always agonized about Holy Week posts. I feel a special duty to contribute what little I can to the Church’s volume of reflection on the meaning of this week.

Though I have little in the way of resources beyond what is in my own mind, I feel an obligation in this of all weeks to “get it right,” and leave something a reader might return to. So I have focused in past Holy Week posts not so much on the meaning of the events of the Passion of the Christ, but on the characters central to those events. In so doing, I have developed a rather special kinship with some of them.

I hope readers will spend some time with them this week by revisiting my Holy Week tributes to “Simon of Cyrene, Compelled to Carry the Cross,” and “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.” I wrote a follow-up to that one in a subsequent Holy Week post entitled, “Pope Francis, the Pride of Mockery, and the Mockery of Pride.” Last year in Holy Week, I visited a haunting work of art fixed upon the wall of my prison cell in “Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands.”

Lifting these characters out of the lines of the Gospel into the light of my quest to know them has enhanced a sense of solidarity with them. This has never been truer than it is for the subject of this year’s TSW Holy Week post. Any believer whose reputation has been overshadowed by innuendos of a past, anyone who stands in possession of a truth that must be told, but is denied the social status to be believed will marvel at the faith and courage of Mary Magdalene.

Her Demon Haunted World

First, a word about language. You might note that I always use the Aramaic term, “Golgotha,” instead of the more familiar “Calvary” for the place where Jesus was crucified. Aramaic is closely related to Hebrew. It became the language of the Middle East sometime after the fall of Nineveh in 612 B.C., and was the language of Palestine at the time of Jesus. Jesus spoke in Aramaic, and so did his disciples.

The Aramaic word, “Golgotha” means “place of the skull.” When the Roman Empire occupied Palestine in 63 B.C., it used that place for crucifixions. It isn’t certain whether that is the origin of the name “Golgotha” or whether the hill resembles a skull from some vantage point. The Gospels were written in Greek, so the Aramaic “Golgotha” was translated “Kranion,” Greek for “skull.” Then in the Fourth and early Fifth Century, Saint Jerome translated the Greek Gospels into Latin using the term, “Calvoriae Locus” for “Place of the Skull.” That’s how the name “Calvary” entered Christian thought.

Mary Magdalene is one of only two figures in the Gospel to have been present with Jesus during his public ministry, at the foot of the Cross at Golgotha, and in his resurrection appearances at and after the empty tomb. The sole other figure was John, the Beloved Disciple. Mary the Mother of Jesus was also present at the Cross, but there is no mention of her at the empty tomb. In the Gospel of Saint Luke, the Twelve were with Jesus during his public ministry …

“… also some women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities, Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna the wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward, and Suzanna, and many others who provided for them out of their means.”

The presence of these women openly challenged Jewish customs and mores of the time which discouraged men from associating with women in public. Add to this the fact that these particular women “had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities” could have set the community abuzz with whispers at their presence with Jesus. In the Gospel of John (4:27), the Apostles came upon Jesus talking with a woman of Samaria at Jacob’s well, and they “marveled that he was talking with a woman.”

A revelation that seven demons had gone out of Mary Magdalene is in no way suppressed by the Gospel writer. On the contrary, it seems the basis of her undying fidelity to the Lord. The Gospel of Saint Mark adds that account in the most unlikely place — the one place where Mary’s credibility seems a necessity, the first Resurrection appearance:

“Now when he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene from whom he had cast out seven demons. She went and told those who had been with him, as they mourned and wept. But when they heard he was alive and had been seen by her, they would not believe it.”

In all four of the Gospel accounts, it was Mary Magdalene who first discovered and announced the empty tomb, and in all four places the announcement sowed doubt, and even some propaganda. In the Gospel of Matthew (28:1-10), “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to the tomb … .” There they were met by an angel who instructed them, “Go quickly and tell his disciples that he has risen from the dead and behold, he is going before you to Galilee.”

Then, in Saint Matthew’s account, Jesus appeared to them on the road and said, “Do not be afraid. Go and tell my brethren to go to Galilee, and there they will see me.” Put yourself in Mary Magdalene’s shoes. She, from whom he cast out seven demons; she, who watched him die a gruesome death, is to find Peter, tell this story, and expect to be believed?

Immediately after in the Gospel of Matthew, the Roman guards went to Caiaphas the High Priest with their own story of what they witnessed at the tomb. Like the thirty pieces of silver used to bribe Judas, Caiaphas paid the guards to spread an alternate story:

“Go report to Pilate that Jesus’ disciples came and stole his body while the guards slept…’ This story has been spread among the Jews even to this day”

Apostle to the Apostles

It makes perfect sense. I, too, have seen “truth” reinvented when there is money involved. Remember that Mary Magdalene is a woman alone, with demons in her past, and she must convey her amazing account to men. So suspect is she as a source that even the early Church overlooked her witness. When Saint Paul related the Resurrection appearances to the Church at Corinth about twenty years later, he omitted Mary Magdalene entirely:

“He appeared to Cephas [the Greek name for Peter], then to the Twelve, then to more than 500 brethren at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James then to all the Apostles. Then last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared to me, for I am the least of the Apostles.”

Saint Paul lists six appearances of Jesus during the forty days between the Resurrection and the Ascension. One of those appearances “to more than 500” appears in none of the Gospel accounts. Saint Paul likely omitted the fact that it was Mary Magdalene from whom news of the Resurrection first arose, and to whom the Risen Christ first appeared, because at that time in that culture, women could not give sworn testimony.

And remember that there was another matter Mary Magdalene had to reconcile before conveying her news. It is the elephant in the upper room. She must not only tell her story to men, but to men who fled Golgotha while she remained. Among all in that room, only Mary Magdalene and the Beloved Disciple John saw Christ die. Peter, their leader, denied knowing Jesus and remained below, listening to a cock crow.

I have imagined another version of Mary Magdalene’s empty tomb report to Peter. I imagined reading it between the lines, but of course it isn’t really there. Still, it’s the version that would have made the most human sense: Mary Magdalene burst into an upper room where the Apostles hid “for fear of the Jews.” She summoned the courage to look Peter in the eye.

Mary M.: “I have good news and not-so-good news.”

Peter: “What’s the good news?”

Mary M.: “The Lord has risen and I have seen him!”

Peter: “And the not-so-good good news?”

Mary M.: “He’s on his way here and he’d like a word with you about last Friday.”

Of course, nothing like that happened. The words of Jesus to Peter about “last Friday” correct his three-time denial with a three-time commission of the risen Christ to “feed my sheep.” The Gospel message is built upon values and principles that challenge all our basest instincts for retribution and justice. The Gospel presents God’s justice, not ours.

Of the four accounts of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection Appearances, the Gospel of John conveys perhaps the most painful, beautiful, and stunning portrait of Mary Magdalene, all written between the lines:

“Standing by the Cross of Jesus were his mother, his mother’s sister [possibly Salome, mother of James and John], Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene.”

Also standing there is John, the Beloved Disciple, and Mary Magdalene becomes a witness to one of the most profound scenes of Sacred Scripture. Jesus addressed his mother from the Cross, “Woman, behold your son.” Is it a reference to himself or to the young man standing next to his mother? Is it both? Standing just feet away, the woman from whom he once cast out seven demons is fixated by what is taking place here. “Behold your Mother!” he says among his last words from the Cross, bestowing upon John — and all of us by extension — the gifts of grace and the care of his mother.

“Woman, Why Are You Weeping?”

“From that point on, John took her into his home,” and we took her into the home of our hearts. Mary Magdalene could barely have dealt with this shattering scene as her Deliverer died before her eyes when, on the morning of the first day of the week, she stood weeping outside his empty tomb. “Woman, why are you weeping?” Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI wrote of this scene from the Gospel of John in his beautifully written book, Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week (Ignatius Press, 2011):

“Now he calls her by name: ‘Mary!’ Once again she has to turn, and now she joyfully recognizes the risen Lord whom she addresses as ‘Rabboni,’ meaning ‘teacher.’ She wants to touch him, to hold him, but the Lord says to her, “Do not hold me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father” (John 20:17). This surprises us…. The earlier way of relating to the earthly Jesus is no longer possible.”

Hippolytus of Rome, a Third Century Father of the Church, called Mary Magdalene an “apostle to the Apostles.” Then in the Sixth Century, Pope Gregory the Great merged Mary Magdalene with the unnamed “sinful woman” who anointed Jesus in the Gospel of Luke (7:37), and with Mary of Bethany who anointed him in the Gospel of John (12:3). This set in motion any number of conspiracy theories and unfounded legends about Jesus and Mary Magdalene that had no basis in fact.

The revisionist history in popular books like The Da Vinci Code, and other novels by New Hampshire author Dan Brown, was contingent upon Mary Magdalene and these two other women being one and the same. The Gospel provides no evidence to support this, a fact the Church now accepts and promotes. This faithful and courageous woman at the Empty Tomb was rescued not only from her demons, but from the distortions of history.

“While up to the moment of Jesus’ death, the suffering Lord had been surrounded by nothing but mockery and cruelty, the Passion Narratives end on a conciliatory note, which leads into the burial and the Resurrection. The faithful women are there…. Gazing upon the Pierced One and suffering with him have now become a fount of purification. The transforming power of Jesus’ Passion has begun.”

+ + +

Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands

“Ecce Homo!” An 1871 painting of Christ before Pilate by Antonio Ciseri depicts a moment woven into the fabric of salvation history, and into our very souls.

“Ecce Homo!” An 1871 painting of Christ before Pilate by Antonio Ciseri depicts a moment woven into the fabric of salvation history, and into our very souls.

“So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd saying, ‘I am innocent of this righteous man’s blood.’”

A now well known Wall Street Journal article, “The Trials of Father MacRae” by Dorothy Rabinowitz (May 10, 2013) had a photograph of me — with hair, no less — being led in chains from my 1994 trial. When I saw that photo, I was drawn back to a vivid scene that I wrote about during Holy Week two years ago in “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.” My Holy Week post began with the scene depicted in that photo and all that was to follow on the day I was sent to prison. It was the Feast of Saint Padre Pio, September 23, 1994, but as I stood before Judge Arthur Brennan to hear my condemnation, I was oblivious to that fact.

Had that photo a more panoramic view, you would see two men shuffling in chains ahead of me toward a prison-bound van. They had the misfortune of being surrounded by clicking cameras aimed at me, and reporters jockeying for position to capture the moment to feed “Our Catholic Tabloid Frenzy About Fallen Priests.” That short walk to the prison van seemed so very long. Despite his own chains, one of the two convicts ahead of me joined the small crowd in mockery of me. The other chastised him in my defense.

Writing from prison 18 years later, in Holy Week 2012, I could not help but remember some irony in that scene as I contemplated the fact of “Dismas, Crucified to the Right.” That post ended with the brief exchange between Christ and Dismas from their respective crosses, and the promise of Paradise on the horizon in response to the plea of Dismas: “Remember me when you come into your kingdom.” This conversation from the cross has some surprising meaning beneath its surface. That post might be worth a Good Friday visit this year.

But before the declaration to Dismas from the Crucified Christ — “Today, you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43) — salvation history required a much more ominous declaration. It was that of Pontius Pilate who washed his hands of any responsibility for the Roman execution of the Christ.

Two weeks ago, in “What if the Prodigal Son Had No Father to Return To?”, I wrote of my fascination with etymology, the origins of words and their meanings. There is also a traceable origin for many oft-used phrases such as “I wash my hands of it.” That well-known phrase came down to us through the centuries to renounce responsibility for any number of the injustices incurred by others. The phrase is a direct allusion to the words and actions of Pontius Pilate from the Gospel of Saint Matthew (27: 24).

Before Pilate stood an innocent man, Jesus of Nazareth, about to be whipped and beaten, then crowned with thorns in mockery of his kingship. Pilate had no real fear of the crowd. He had no reason to appease them. No amount of hand washing can cleanse from history the stain that Pilate tried to remove from himself by this symbolic washing of his hands.

This scene became the First Station of the Cross. At the Shrine of Lourdes the scene includes a boy standing behind Pilate with a bowl of water to wash away Pilate’s guilt. My friend, Father George David Byers sent me a photo of it, and a post he once wrote after a pilgrimage to Lourdes:

“Some of you may be familiar with ‘The High Stations’ up on the mountain behind the grotto in Lourdes, France. The larger-than-life bronze statues made vivid the intensity of the injustice that is occurring. In the First Station, Jesus, guarded by Roman soldiers, is depicted as being condemned to death by Pontius Pilate who is about to wash his hands of this unjust judgment. A boy stands at the ready with a bowl and a pitcher of water so as to wash away the guilt from the hands of Pilate . . . Some years ago a terrorist group set off a bomb in front of this scene. The bronze statue of Pontius Pilate was destroyed . . . The water boy is still there, eager to wash our hands of guilt, though such forgiveness is only given from the Cross.”

The Writing on the Wall

As that van left me behind these stone walls that day nearly twenty years ago, the other two prisoners with me were sent off to the usual Receiving Unit, but something more special awaited me. I was taken to begin a three-month stay in solitary confinement. Every surface of the cell I was in bore the madness of previous occupants. Every square inch of its walls was completely covered in penciled graffiti. At first, it repulsed me. Then, after unending days with nothing to contemplate but my plight and those walls, I began to read. I read every scribbled thought, every scrawled expletive, every plea for mercy and deliverance. I read them a hundred times over before I emerged from that tomb three months later, still sane. Or so I thought.

When I read “I Come to the Catholic Church for Healing and Hope,” Pornchai Maximilian Moontri’s guest post last month, I wondered how he endured solitary confinement that stretched for year upon year. “Today as I look back,” he wrote, “I see that even then in the darkness of solitary confinement, Christ was calling me out of the dark.” It’s an ironic image because one of the most maddening things about solitary confinement is that it’s never dark. Intense overhead lights are on 24/7.

The darkness of solitary confinement he described is only on the inside, the inside of a mind and soul, and it’s a pitch blackness that defies description. My psyche was wounded, at best, after three months. I cannot describe how Pornchai endured this for many years. But he did, and no doubt those who brought it about have since washed their hands of it.

For me, once out of solitary confinement, the writing on the walls took on new meaning. In “Angelic Justice: St Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed” a few years back, I described a section of each cell wall where prisoners are allowed to post the images that give meaning and hope to their lives. One wall in each cell contains two painted rectangles, each barely more than two by four feet, and posted within them are the sole remnant of any individualism in prison. You can learn a lot about a man from that finite space on his wall.

When I was moved into this cell, Pornchai’s wall was empty, and mine remained empty as well. Once These Stone Walls began in 2009, however, readers began to transform our wall without realizing it. Images sent to me made their way onto the wall, and some of the really nice ones somehow mysteriously migrated over to Pornchai’s wall. A very nice Saint Michael icon spread its wings and flew over to his side one day. That now famous photo of Pope Francis with a lamb placed on his shoulders is on Pornchai’s wall, and when I asked him how my Saint Padre Pio icon managed to get over there, he muttered something about bilocation.

Ecce Homo!

One powerful image, however, has never left its designated spot in the very center of my wall. It’s a five-by-seven inch card bearing the 1871 painting, “Ecce Homo!” — “Behold the Man!” — by the Swiss-born Italian artist, Antonio Ciseri. It was sent to me by a TSW reader during Holy Week a few years ago. The haunting image went quickly onto my cell wall where it has remained since. The Ciseri painting depicts a scene that both draws me in and repels me at the same time.

On one dark day in prison, I decided to take it down from my wall because it troubles me. But I could not, and it took some time to figure out why. This scene of Christ before Pilate captures an event described vividly in the Gospel of Saint John (19:1-5). Pilate, unable to reason with the crowd has Jesus taken behind the scenes to be stripped and scourged, a mocking crown of thorns thrust upon his head. The image makes me not want to look, but then once I do look, I have a hard time looking away.

When he is returned to Pilate, as the scene depicts, the hands of Christ are bound behind his back, a scarlet garment in further mockery of his kingship is stripped from him down to his waist. His eyes are cast to the floor as Pilate, in fine white robes, gestures to Christ with his left hand to incite the crowd into a final decision that he has the power to overrule, but won’t. “Behold the Man!” Pilate shouts in a last vain gesture that perhaps this beating and public humiliation might be enough for them. It isn’t.

I don’t want to look, and I can’t look away because I once stood in that spot, half naked before Pilate in a trial-by-mob. On that day when I arrived in prison, before I was thrown into solitary confinement for three months, I was unceremoniously doused with a delousing agent, and then forced to stand naked while surrounded by men in riot gear, Pilate’s guards mocking not so much what they thought was my crime, but my priesthood. They pointed at me and laughed, invited me to give them an excuse for my own scourging, and then finally, when the mob was appeased, they left me in the tomb they prepared, the tomb of solitary confinement. Many would today deny that such a scene ever took place, but it did. It was twenty years ago. Most are gone now, collecting state pensions for their years of public service, having long since washed their hands of all that ever happened in prison.

Behold the Man!

I don’t tell this story because I equate myself with Christ. It’s just the opposite. In each Holy Week post I’ve written, I find that I am some other character in this scene. I’ve been “Simon of Cyrene, Compelled to Carry the Cross.” I’ve been “Dismas, Crucified to the Right.” I tell this story first because it’s the truth, and second because having lived it, I today look upon that scene of Christ before Pilate on my wall, and I see it differently than most of you might. I relate to it perhaps a bit more than I would had I myself never stood before Pilate.

Having stared for three years at this scene fixed upon my cell wall, words cannot describe the sheer force of awe and irony I felt when someone sent me an October 2013 article by Carlos Caso-Rosendi written and published in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the home town of Pope Francis. The article was entitled, “Behold the Man!” and it was about my trial and imprisonment. Having no idea whatsoever of the images upon my cell wall, Carlos Caso-Rosendi’s article began with this very same image: Antonio Ciseri’s 1871 painting, “Ecce Homo!” TSW reader, Bea Pires, printed Carlos’ article and sent it to Pope Francis.

I read the above paragraphs to Pornchai-Maximilian about the power of this scene on my wall. He agrees that he, too, finds this image over on my side of this cell to be vaguely troubling and disconcerting, and for the same reasons I do. He has also lived the humiliation the scene depicts, and because of that he relates to the scene as I do, with both reverence and revulsion. “That’s why it stay on your wall,” he said, “and never found its way over to mine!”

Aha! A confession!