“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night

Prayers for justice, for the fall of prison walls, are prayers for hope. On the night hope fell, Fr Benedict Groeschel served upon me a summons from the Highest Court.

Prayers for justice, for the fall of prison walls, are prayers for hope. On the night hope fell, Fr Benedict Groeschel served upon me a summons from the Highest Court.

I don’t think I have ever struggled with a post as I struggle now with this one. It is painful to write, and, in part at least, I know it will be painful to read. What I am about to describe is an earlier scene in the story of my own passion narrative that you do not know about, and now it is time to put it openly before you. I only ask you to withhold judgment for the judgment on this story is not yours to have. And I ask that you bear with me to the end for, as you will read, that is exactly what I am doing.

This confession of sorts was prompted by the 54-day Rosary Novena in which so many readers of Beyond These Stone Walls are engaged on my behalf. Many others who could not commit to that effort are offering prayers and sacrifices for those who are. Some include our friend, Pornchai Maximilian Moontri in these prayers, and I am most grateful for that. I mentioned in a post two weeks ago that I have been simply lost for words by this outpouring of faith and hope, and I will have something to say about it in my post this week.

But that was not entirely true. I have not been as “lost for words” as I claimed. It’s just that the words that come, the words that I must convey to you now, are from a time when my own faith and hope fell into the darkest of nights, and I fear you may think less of me for it. That is what I risk for total candor, but I risk far more if I do not speak up.

When my post, “Seven Years Behind These Stone Walls” appeared on BTSW on June 29, some readers surprised me with an overture to begin a 54-Day Rosary Novena for the cause of justice. It was to begin on the following day, June 30, the Commemoration of the First Martyrs of the Church of Rome.

Your prayer for me is much more a prayer for hope, and you may have no idea how much that prayer is needed. Most have no idea how fragile hope can be for the falsely accused. BTSW reader, Helen, sent me a note asking if I am conscious of the prayer support of so many. What I have been most conscious of is what happened on the morning this Rosary Novena began.

At 3:00 AM that Thursday morning, June 30th, I was awakened in my cell from a very vivid and troubling dream. You know that in February I underwent surgery and now have a seven-inch scar extending under my ribcage from the front to my side. In the dream, I woke up with a strange sensation. I lifted my shirt to discover with horror that my scar had opened and blood and water were pouring out from it drenching everything. It was not water mixed with blood. Both were streaming out of the open wound, blood on one side and water on the other. I tried to put my hand over it to stop it, but the flow continued right through my hand. It went on for a long time, and in my subconscious mind this was somehow connected with your prayers.

When I finally awoke for real, I quickly sat up and lifted my shirt. I grabbed my book light and a mirror, but all was dry and the scar was sealed and intact. It was a little after 3:00 AM and I was filled with anxiety and had trouble breathing.

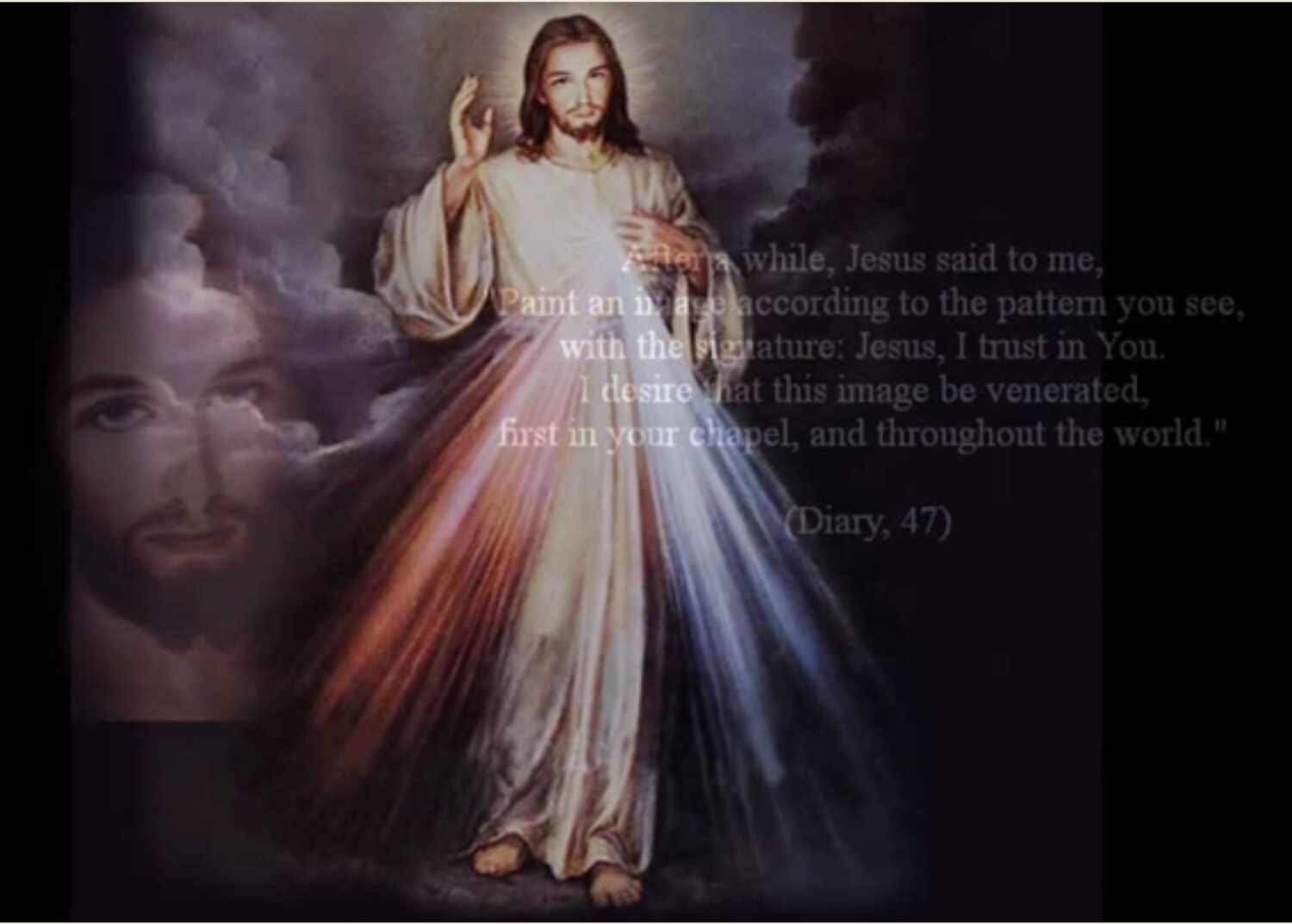

So I got up and paced around this cell. Soon after, Pornchai was awakened in the bunk above me. He asked me what was wrong. I was shaken, but I told him about the dream. As I spoke, he glanced over my shoulder at the Divine Mercy image on our cell wall. Pornchai got it immediately, but I am a little slow in such matters. Saint Faustina wrote:

“During prayer I heard these words within me: The two rays denote Blood and Water. The pale ray stands for the Water which makes souls righteous. The red ray stands for the Blood which is the life of souls... These two rays issued forth from the very depth of my tender mercy when my agonized heart was pierced by a lance on the Cross.… Happy is the one who will dwell in their shelter for the just hand of God shall not lay hold of him.”

— Diary of Saint Faustina, 299

Later that morning, I called Father George David Byers and told him about this dream. It was only then that I connected it with an event in the Gospel of John (19:34), “But one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once there came out blood and water.” Please do not misunderstand me. I have no messianic delusions whatsoever. Christ asked, and I merely fled. The first stunning lines of Francis Thompson’s haunting, “The Hound of Heaven” capture best what happened when I was first issued a summons to Divine Mercy:

“I fled him, down the night and down the days; I fled him, down the arches of the years; I fled him, down the labyrinthine ways of my own mind; and in the midst of tears, I hid from him.”

Christ at the Crossroads

A note on John 19:34 describes the flow of blood and water as evidence of Christ’s humanity, that place where His life and that of fallen humanity intersects. The dream has stayed with me through the days of your prayers, and I find it to be both scary and hopeful. The hardest, most unrepentant criminal here fears only one thing: dying in prison. You can imagine then the toll that such a prospect takes on someone wrongfully imprisoned.

So of course I want your prayers to have real meaning, and to succeed despite the fact that I am not worthy of them. I am not worthy of them because there was a time in my life when, on the night of my own Gethsemane, faith and hope utterly failed me and I fell. In my hopelessness, I attempted to take my own life, and was hospitalized for it.

I have to try to convey the context. It was May of 1993, weeks after I had been accused. At the time, ironically, I served in ministry as Director of Admissions of the New Mexico Servants of the Paraclete residential center for priests.

There is no point in the details, but what I did was serious, and deadly, and I should not have survived it. But I did survive. It is one thing for someone justly accused to face such charges, but to be falsely accused, summarily declared guilty by my own bishop and diocese, disposed for the sake of thirty pieces of silver, is devastating for a priest.

Complicating this picture was the fact that I have epilepsy — specifically, complex-partial seizure disorder with a focus bilaterally in the temporal lobes. That, combined with the crushing experience of being falsely accused and discarded, swept away in a moment of despair all frame of reference for my life as a priest, and left me drained of all resources.

This was a time when the U.S. church was reeling over the sudden emergence of many such claims from decades past, and many in the Church pretended to believe them all just to ease the path to quick, quiet financial settlement. It was the dawn of what Father George David Byers described as “The Judas Crisis.” As my broken spirit descended into chaos, I believed that a sacrifice was required, the sacrifice of the life of a priest, and I believed I was to be that sacrifice. It was a moment when all hope went out of my world, and my faith and sanity fell along with it.

By some miracle of actual grace, I survived. On that night late in May of 1993 I regained consciousness in the Intensive Care Unit of Albuquerque Presbyterian Hospital. I did not, for a time, know where, or even who I was, but within a day my mind came back on line as though rebooted. I felt the deepest darkest shame and despair over this shattering of all hope as my life and priesthood lay before me in utter ruins.

My friend, Father Clyde Landry, was there with me. He told me that I had written a letter to the Servant General, Father Liam Hoare, asserting my innocence of these charges, but asking his forgiveness for the sacrifice of my life because of the harm these false claims brought upon priesthood and Church. I do not know what became of that letter.

That night in my hospital room, my friend Father Clyde brought me something that he knew I treasured and might want. It was a portable shortwave radio. Later, when I was alone, still deeply shattered, I turned it on and placed the earpiece in my ear. I randomly turned the dial, then stopped suddenly.

I had used that radio on many nights as I surfed the shortwave band for broadcasts from around the world, but I had never before come across what I heard that night in Gethsemane. I distinctly heard intoned the “Salve Regina,” and then an announcer’s voice that I was listening to EWTN broadcasting on a shortwave band from Irondale, Alabama. Then I heard a clear and very familiar voice. It was the voice of someone I had known well many years earlier, but lost touch with. The lilting voice and Yonkers accent were unmistakable. It was Father Benedict Groeschel.

My Gift to the Lord: An Empty Vessel

Some time ago, I wrote a post in defense of Father Groeschel entitled, “Father Benedict Groeschel at EWTN: Time for a Moment of Truth.” What happened on the night I am now describing is why I wrote that post. He was accused of calling into question a claim of victimhood in the Catholic scandal, and the Gospel of Political Correctness that American bishops had cowardly agreed to was not going to spare him. The wolves began to circle Father Groeschel and several Catholic institutions he so generously served all began to get some distance from him. In my challenging post, I drew a line in the sand that many stood behind. “Not this time! Not this priest!” I wrote.

I wrote that post because twenty years earlier, Father Benedict Groeschel entered my darkest night with a message of hope, and a plan for redemption when all was lost. In that hospital bed that night, it was as though he was addressing me directly. I can only paraphrase it here, and hope that I am doing it justice:

“When life seems as though it has fallen apart, and you face an immeasurable sense of loss, whether the cause is tragic illness, or loss of a loved one, or financial ruin, or public shame, or grave injustice, the loss of all hope seems to be the final loss. It leaves you as though an empty vessel which you feel can never be filled again. This is a crucial and vulnerable time. It is also a moment when God is nearest to you.”

Father Groeschel went on that night to speak of the only response left for an empty vessel: a spirit of abandonment and surrender to God’s Providence. God alone can fill what has been torn asunder by the forces of this world. “Surrender control, for control of your life is an illusion,” he said. “Embrace surrender to God’s Providence so that your empty vessel may serve Him in the salvation not just of your soul, but of many souls.” I was, for perhaps the first time in my life, ready to hear these words and absorb them. Nothing made sense up to then, but Father Groeschel made total sense.

You may remember a post of mine about the suicide of another priest from my diocese, Father Richard Lower. I wrote of this tragedy in “The Dark Night of a Priestly Soul.” After being informed by Monsignor Edward Arsenault of the emergence of a decades-old sexual abuse claim, Father Lower was given the usual 24 hours to vacate his parish and residence without a word to his parishioners whom he had served for a dozen years. He was to be just another priest who disappears in the night. In his darkest night, he walked out to a deserted mountain path and took his own life. In “The Dark Night of a Priestly Soul” I wrote that I would have given anything to have been on that path with him. It’s because I HAVE been on that path, and I survived.

Some twenty-six accused U.S. Catholic priests have taken their own lives since the U.S. Bishops entered into The Judas Crisis by presuming every money-driven claim against a priest to be true. Whatever cynic presumes from this their guilt knows nothing of the identity of priesthood and its permanent bond with the notion of sacrifice. No priest should be required to sacrifice his life to satisfy the demands of contingency lawyers, insurance companies, and the agendas of those who despise the Church.

The Summons of Divine Mercy

The summons served upon me by Father Benedict Groeschel that night came from the Highest Court of justice, a Court in which Divine Mercy is its mirror image. It was actually the second time that summons was served. The first time was exactly one month earlier. A friend and coworker in the Servants of the Paraclete ministry to priests was Father Richard Drabik, MIC. He was also my spiritual director. You may recognize him as the former Provincial Superior of the Marian Fathers of the Immaculate Conception, and the author of the Preface to the Diary of Saint Maria Faustina.

In early April, 1993, Father Drabik came to my office with a request. He was leaving for Rome a week later to concelebrate Mass at the Beatification of (then) Blessed Faustina on Divine Mercy Sunday, April 18, 1993. Father Drabik invited me to draft a petition that he would place on the altar at the Beatification. The petition I wrote was this simple note sealed in a small envelope:

“I ask for the intercession of Blessed Faustina that I may have the courage to be the priest God intends for me to be.”

Fifteen days after the Beatification, I was charged with crimes alleged to have taken place over a decade earlier, crimes that never took place at all, and the violent emptying of the vessel of my life and priesthood began. Two weeks later, the courage I asked for gave way to hopelessness as I lay in ICU hearing this summons repeated by Father Benedict Groesechel.

So on that awful night, I solemnly vowed to go the distance, to remain an empty vessel with hope and trust as my only choices in life while discerning God’s Providence. Since then, as you know if you have been an attentive reader of Beyond These Stone Walls, that summons to Divine Mercy has become woven into every fiber of my life, and not only my life, but many others.

The stunning evidence for this is found in many places, but one of the more striking is the medical miracle confirmed as attributed to Saint Faustina by the Vatican Congregation for the Cause of Saints. The recipient of that miracle was Mrs. Maureen Digan who shares a chapter along with Pornchai Moontri in Felix Carroll’s wondrous book, Loved, Lost, Found: 17 Divine Mercy Conversions. Seeing Pornchai’s and Maureen’s stories together in that volume is to see Divine Mercy come full circle in my life and priesthood, and this empty vessel filled with hope beyond imagining. I thank you for your heroic prayers for justice on my behalf. The most fundamental aspect of justice is the preservation of hope.

“O Blood and Water which gushed forth from the Heart of Jesus as Fount of Mercy for us, I trust in You.”

— Diary of Saint Faustina, 309

“To priests who proclaim and extol My mercy, I will give wondrous power; I will anoint their words and touch the hearts of those to whom they will speak.”

— Diary of Saint Faustina, 1521

+ + +

Editor’s Note: This post continues next week on Beyond These Stone Walls with “Saint Maximilian Kolbe: A Knight at My Own Armageddon.”

And with joy and thanksgiving, Father Gordon MacRae wants you to know about the publication of an inspiring biography, A Friar’s Tale: Remembering Father Benedict J.Groeschel, C.F.R. by John Collins available from Our Sunday Visitor.

A Friar’s Tale — Remembering Fr. Benedict J. Groeschel by John Collins (Our Sunday Visitor)

The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts

The concept of Purgatory is repugnant to those who do not understand Scripture, and a source of fear for many who do, but beyond the Cross, it is a source of hope.

The concept of Purgatory is repugnant to those who do not understand Scripture, and a source of fear for many who do, but beyond the Cross, it is a source of hope.

All Souls Day

Twenty-four hours after this is posted, it will no longer be All Souls Day. I risk losing everyone’s interest as we all move on to the daily grind of living. But I am not at all concerned. We’re also in the daily grind of dying. Death is all around us — it’s all around me, at least — and never far from conscious concern. Death was part of the daily prayer of Saint Padre Pio as well:

“Stay with me, Lord, for it is getting late; the days are coming to a close and life is passing. Death, judgment and eternity are drawing near.”

I have never feared death. At least, I have never feared the idea of dying. It’s just the inconvenience of it that bothers me most, not knowing when or how. The very notion of leaving this world with my affairs undone or half done is appalling to me. The thought that Someone knows of that moment but won’t share this news with me makes me squirm. “You know not the day nor the hour” (Matthew 24:36) is, for me, one of the most ominous verses in all of Scripture.

But even when a lot younger, I never thought I would have to be dragged kicking and screaming out of this life and into the next one. I think it’s because I have always had a strong belief in Purgatory. It’s one of the most wonderful and hopeful tenets of the Catholic faith that salvation isn’t necessarily a black and white affair driven solely by the peaks and valleys of this life. I have never been so arrogant as to believe that my salvation is a done deal. I have also never been so self-deprecating as to believe that God waits for the extinction of both our lives and our souls.

It is the mystery of “Hesed,” the balance of justice with mercy that I wrote of in “Angelic Justice,” that is the foundation of Purgatory. In God’s great Love for us, and in His Divine Mission to preserve that part of us that is in His image and likeness — something this world cannot possibly do — God has left a loophole in the law. It’s a way for sinners who love and trust Him, and seek to know Him, to come to Him through Christ to be redeemed. The very notion of Purgatory fills me with hope, and I’m hoping for it. It’s largely because of Purgatory that I do not fear death.

All Souls Day was first observed in the Catholic Church in the monastery of Cluny in France in the year 998. It was originally about Purgatory, and not just death. The monks at Cluny set aside the day after the Feast of All Saints — which began two centuries earlier — to devote a day of prayer and giving alms to assist the souls of our loved ones in Purgatory. In the Second Book of Maccabees (12:46) Judas Maccabeus “made atonement for the dead that they might be delivered from their sin.”

Purgatory itself has, since the earliest Christian traditions, been a tenet of faith in which the souls of those who have left this world in God’s friendship are purified and made ready for the Presence of God. The Eastern and Latin churches agree that it is a place of intense suffering, and I’m looking forward to my stint.

Okay, I’ll admit that sounds a little weird. It isn’t as though seventeen years in prison has conditioned me for ever more punishment. I do not find punishment to be addictive at all, especially when I did not commit the crime. The punishment of Purgatory, however, is something I know I cannot evade. The intense suffering of Purgatory is entirely a spiritual suffering, and it begins with our experience of death right here. The longing with which we sometimes agonize over the loss of those we love is but a shadow of something spiritual we have yet to share with them: The Holy Longing they must endure as they await being in the Presence of God. That Holy Longing is Purgatory. It is the delay of the beatific vision for which we were created, and that delay and its longing is a suffering greater than we can imagine.

Death, Drawing Near

Years ago, an old friend came to me after having lost his wife of sixty years. I could only imagine what this was like for him. After her funeral and burial all his relatives finally went home, and he was alone in his grief. When we met, he told me of the intensity of his suffering. My heart was broken for him, but something in his grief struck me. I asked him not to waste this suffering, but rather to see it as a part of the longing his dear wife now has as she awaits her place in the fullness of God’s Presence. I suggested that his longing for her was but a shadow of her intense longing for God and perhaps they could go through this together. I asked him to offer his daily experience of grief for the soul of his wife.

He later told me that this advice sparked something in him that made him embrace both his grief and his loss by seeing it in a new light. Every moment in those first days and weeks and months without her was an agony that he found himself offering for her and on her behalf. He said this didn’t make any of his suffering go away, but it filled him with hope and a renewed sense of purpose. It gave meaning to his suffering which would otherwise have seemed empty.

Though I could not possibly relate to his loss, I know only too well the experience of being stranded by the deaths of others. In early Advent last year, I wrote “And Death’s Dark Shadow Put to Flight.” The title was a line from the hauntingly beautiful Advent hymn, “0 Come, 0 Come Emmanuel” that we will all be hearing in a few weeks.

That post, however, was about the death of Father Michael Mack, a Servant of the Paraclete, a co-worker, and a dear friend who was murdered in the first week of Advent. It was ten years ago this December 7th. It was a senseless death — by our standards, anyway — brought upon this 60-year-old priest and good friend by Stephen A. Degraff, a young man who took Father Mike’s life for the contents of his wallet. A part of my share in his Purgatory was to pray not only for Michael Mack, but for Stephen Degraff as well.

On the evening of December 7, 2001, Father Michael Mack returned to his home after some time helping out in a remote New Mexico diocese. Saint Paul wrote that “the Day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night” (1 Thessalonians 5:2). For Father Michael, it did just that. But for me in prison 2,000 miles away, awareness of this loss took time. No one can telephone me in prison, and I can usually only be reached by mail. It turned out that Father Michael sat at a desk in his home and wrote a letter to me on the night he died — all the while oblivious to the danger lurking in a closet in that same room. Father Mike took the letter outside to his mailbox and then walked back inside and into the moment of his death.

Three days later, after prison mail call, I sat at a small table outside my cell with the letter from Father Mike in my hands. I was so glad to hear from him. As I sat there reading the letter with a smile on my face, another prisoner asked if I wanted to see the previous day’s Boston Globe. With Father Mike’s letter in my left hand, I absentmindedly turned to page two of the Globe to see a tiny headline under National News: “New Mexico priest murdered.” Father Michael Mack’s name jumped from the page, and a part of me died just there.

All the Catholic rituals through which we bid farewell and accept the reality of death in hope are denied to a prisoner. I had only that last letter describing all Father Mike’s hopes and dreams and renewed energy for a priestly ministry to other wounded priests. Then after he signed it and scribbled in a PS — “Looking forward to hearing from you” — he walked right into his death.

This wasn’t the last time such a thing happened. This is the 18th time I mark All Souls Day in prison, and the list of souls I once knew in this life — and still know — has grown longer. In “A Corner of the Veil,” I wrote of the death of my mother — imprisoned herself during three years of grueling sickness just seventy miles from this prison, but I could not see her, speak with her, or assure her in any way except through letters that could not be answered. She died five years ago this November 5th. Last week, I received a letter from TSW readers Tom and JoAnn Glenn which included a beautiful photograph of my mother imprinted on a prayer card. They found the photograph on line. I had never seen it, and was so grateful that they sent this to me.

No news of death has ever come to me with more devastation than that of my friend, Father Clyde Landry. Father Mike Mack, Father Clyde, and I were co-workers and good friends, sharing office space in the years we worked in ministry to wounded priests at the Servants of the Paraclete Center in New Mexico. I was Director of Admissions and Father Clyde was Director of Aftercare. A priest of the Diocese of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Father Clyde had a Cajun accent reminiscent of that famous Cajun television chef, Justin Wilson — “I Gar-on-TEE!”

The Dark Night of the Soul

On that night of Gethsemane when I was falsely accused and arrested, it was Father Clyde who first came to my aid, and stood by me throughout. When I was sent to prison, Father Clyde became my lifeline to the outside world. I called him every Saturday. It became a part of my routine, like clockwork. It was through Father Clyde that once a week I reached out to the outside world for news of friends and news of freedom. He held a small account for me to help with expenses such as telephone costs, food and clothing, small things that make a prisoner’s life more bearable. Most important of all, Father Clyde volunteered to be the keeper of everything of value that I owned.

By “everything of value,” I do not mean riches. I never had any. He kept the Chalice that was given to me at priesthood ordination. He kept the stoles that were made for me, and the small things that were dear to my life and priesthood.

He kept the irreplaceable photos of my parents — both gone now — and all the things that were a lifetime’s proof of my own existence. Everything that I left behind for prison hoping to one day see again was in the possession of Father Clyde.

A year after Father Michael Mack’s tragic death, I received a joyous letter from Father Clyde. He had a new life in ministry as administrator of a very busy retreat center in New Mexico, and he was looking forward to starting. He had also purchased a small home near the center in a beautiful part of Albuquerque. It was the first time in his 52 years that he had owned any home. It was a sign of the stability that he longed for, and a sign of his great love for the retreat ministry he was undertaking.

Father Clyde’s letter was very careful to include me in this transition. He had packed all my possessions and would place them in his spare room which he promised would be available to me whenever I was released from my nightmare. His letter was the last he wrote from his vacant apartment, all his boxes stacked just next to him. He wanted me to know that by the time I received his letter he would be moved and settled and ready for my call the following Saturday.

I received Father Clyde’s letter on a Friday evening, and tried to call his new number the next day. I got only a recorded message that the number was disconnected. In prison, no one can call me and I am unable to leave messages on any answering machine or voice mail. So I called another friend to ask if he would please send an e-mail message for me. My friend fired up his computer and asked, “Where’s it going?” I gave him the e-mail address and started my message.

“Hello Clyde,” I said. “I hope you are getting settled.” Instead of hearing the clicks of my friend’s keyboard, however, I heard only silence. He wasn’t typing. I asked him what was wrong, and knew instantly from his hesitation that something was very wrong.

“Oh, My God!” he said. “You don’t know!” He then told me that my friend, Father Clyde, never made it to his new home. When he did not show up for the signing appointment with his realtor, a search was underway. Father Clyde was found in his apartment on the floor next to the last box he had packed. At age 52, he had suffered a fatal heart attack.

Father Clyde had been gone three days by the time I learned this. No one could reach me. With Father Clyde’s letter in my left hand, I was stunned as my friend described all he knew of Father Clyde’s death, which wasn’t much. It would be many days before I could learn anything more.

In the weeks and months to follow, I was stranded in a way that I had never experienced before. I was not just alone in my grief. I was alone in prison, 2,000 miles from the world I knew and the only contacts I had, and my sole connection with the outside world was gone. It would be another seven years before the idea of These Stone Walls emerged, and I would once again reach out from prison to the outside world.

But for those seven years, I was stranded. On the Saturday after I learned of Fr. Clyde’s death, I recall sitting in my cell from where I could see the bank of prisoner telephones along one wall out in the dayroom, and I cried for the first time in many, many years. In the months to follow, everything that I once hoped one day to see again was lost. I do not know what became of any of Father Clyde’s things, or my own. I have come to know that this happens to many prisoners. Cut off from the world outside, our losses can be catastrophic.

But I came to know that grief is a gift, and I have offered it not only for the souls of Fathers Clyde, Mike, and Moe — and for my dear mother — but for the souls of all who touched my life, and in that offering I had something to share with them — a Holy Longing.

When I wrote “The Dark Night of a Priestly Soul,” it was about Purgatory. It was about my continued hope for the soul of Father Richard Lower, a brother priest driven to take his own life in a dark night all alone when all trust was broken and hope seemed but a distant dream. I have been where he was, and my response to his death was “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”

At the end of “The Dark Night of a Priestly Soul,” I included a portion of the “Prayer of Gerontius” by Blessed John Henry Newman. It’s a beautiful verse about Purgatory that calls forth the abiding hope we have for our loved ones who have died, and also recalls that one thing we have left to share with them — a Holy Longing for their presence, and, in their company, for the Presence of God:

Softly and gently, dearly-ransomed soul,

In my most loving arms I now enfold thee,

And, o’er the penal waters, as they roll,

I poise thee, and I lower thee, and hold thee.

And carefully, I dip thee in the lake,

And thou, without a sob or a resistance,

Dost through the flood thy rapid passage take,

Sinking deep, deeper, into the dim distance.

Angels, to whom the willing task is given,

Shall tend, and nurse, and lull thee, as thou liest;

And Masses on the Earth and prayers in Heaven,

Shall aid thee at the throne of the most Highest.

Farewell, but not forever! Brother dear;

Be brave and patient on thy bed of sorrow;

Swiftly shall pass thy night of trial here,

And I will come and wake thee on the morrow.

— John Henry Cardinal Newman, Conclusion, “The Prayer of Gerontius”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading. Please share this post so that it may come before someone who is grieving. You may also wish to read these related posts linked herein:

Angelic Justice: Saint Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed