“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Mary Magdalene: Faith, Courage, and an Empty Tomb

History unjustly sullied her name without evidence, but Mary Magdalene emerges from the Gospel a faithful, courageous and noble woman, an apostle to the Apostles.

History unjustly sullied her name without evidence, but Mary Magdalene emerges from the Gospel a faithful, courageous and noble woman, an apostle to the Apostles.

As an imprisoned priest, a communal celebration of the Easter Triduum is not available to me. My celebration of this week is for the most part limited to a private reading of the Roman Missal. Still, over the five-plus years that I have been writing for These Stone Walls, I have always agonized about Holy Week posts. I feel a special duty to contribute what little I can to the Church’s volume of reflection on the meaning of this week.

Though I have little in the way of resources beyond what is in my own mind, I feel an obligation in this of all weeks to “get it right,” and leave something a reader might return to. So I have focused in past Holy Week posts not so much on the meaning of the events of the Passion of the Christ, but on the characters central to those events. In so doing, I have developed a rather special kinship with some of them.

I hope readers will spend some time with them this week by revisiting my Holy Week tributes to “Simon of Cyrene, Compelled to Carry the Cross,” and “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.” I wrote a follow-up to that one in a subsequent Holy Week post entitled, “Pope Francis, the Pride of Mockery, and the Mockery of Pride.” Last year in Holy Week, I visited a haunting work of art fixed upon the wall of my prison cell in “Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands.”

Lifting these characters out of the lines of the Gospel into the light of my quest to know them has enhanced a sense of solidarity with them. This has never been truer than it is for the subject of this year’s TSW Holy Week post. Any believer whose reputation has been overshadowed by innuendos of a past, anyone who stands in possession of a truth that must be told, but is denied the social status to be believed will marvel at the faith and courage of Mary Magdalene.

Her Demon Haunted World

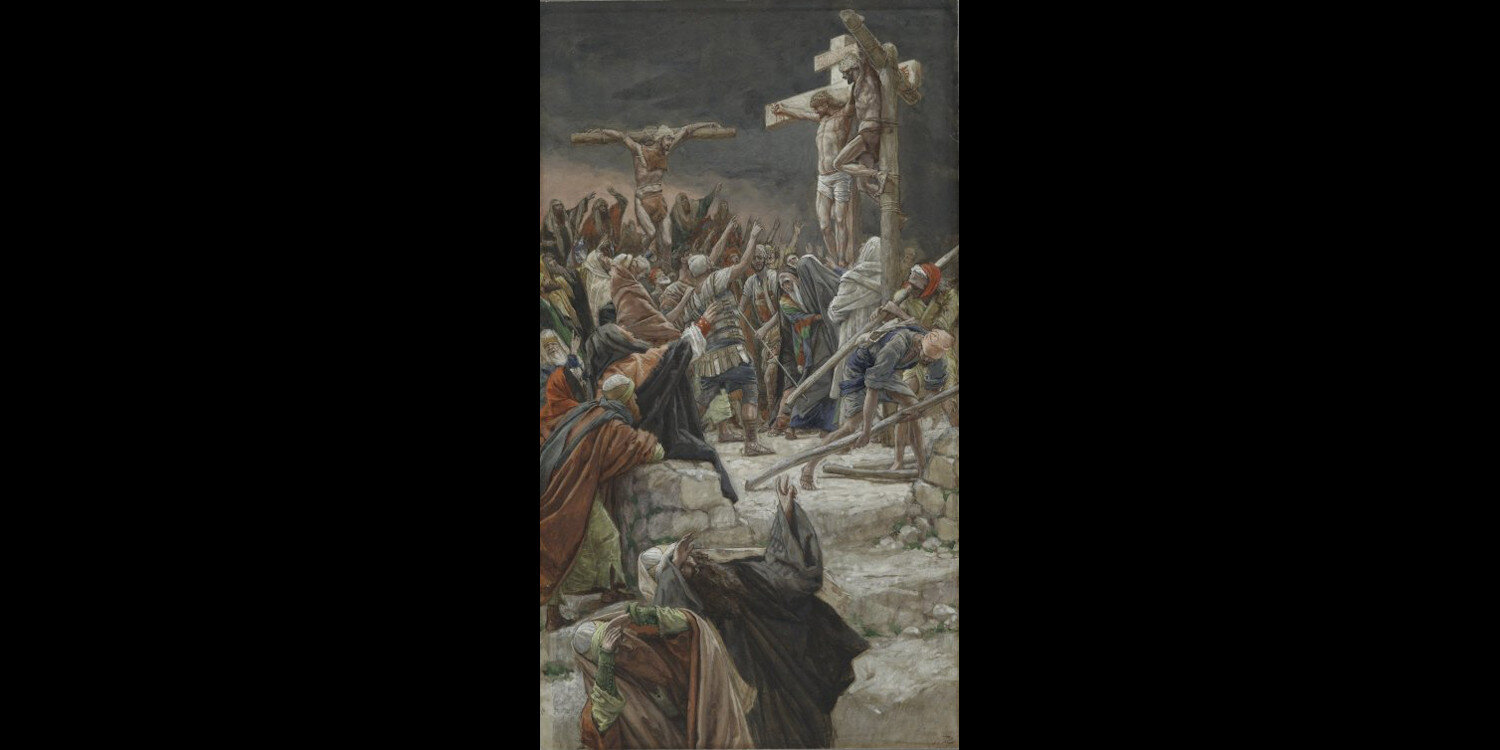

First, a word about language. You might note that I always use the Aramaic term, “Golgotha,” instead of the more familiar “Calvary” for the place where Jesus was crucified. Aramaic is closely related to Hebrew. It became the language of the Middle East sometime after the fall of Nineveh in 612 B.C., and was the language of Palestine at the time of Jesus. Jesus spoke in Aramaic, and so did his disciples.

The Aramaic word, “Golgotha” means “place of the skull.” When the Roman Empire occupied Palestine in 63 B.C., it used that place for crucifixions. It isn’t certain whether that is the origin of the name “Golgotha” or whether the hill resembles a skull from some vantage point. The Gospels were written in Greek, so the Aramaic “Golgotha” was translated “Kranion,” Greek for “skull.” Then in the Fourth and early Fifth Century, Saint Jerome translated the Greek Gospels into Latin using the term, “Calvoriae Locus” for “Place of the Skull.” That’s how the name “Calvary” entered Christian thought.

Mary Magdalene is one of only two figures in the Gospel to have been present with Jesus during his public ministry, at the foot of the Cross at Golgotha, and in his resurrection appearances at and after the empty tomb. The sole other figure was John, the Beloved Disciple. Mary the Mother of Jesus was also present at the Cross, but there is no mention of her at the empty tomb. In the Gospel of Saint Luke, the Twelve were with Jesus during his public ministry …

“… also some women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities, Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna the wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward, and Suzanna, and many others who provided for them out of their means.”

The presence of these women openly challenged Jewish customs and mores of the time which discouraged men from associating with women in public. Add to this the fact that these particular women “had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities” could have set the community abuzz with whispers at their presence with Jesus. In the Gospel of John (4:27), the Apostles came upon Jesus talking with a woman of Samaria at Jacob’s well, and they “marveled that he was talking with a woman.”

A revelation that seven demons had gone out of Mary Magdalene is in no way suppressed by the Gospel writer. On the contrary, it seems the basis of her undying fidelity to the Lord. The Gospel of Saint Mark adds that account in the most unlikely place — the one place where Mary’s credibility seems a necessity, the first Resurrection appearance:

“Now when he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene from whom he had cast out seven demons. She went and told those who had been with him, as they mourned and wept. But when they heard he was alive and had been seen by her, they would not believe it.”

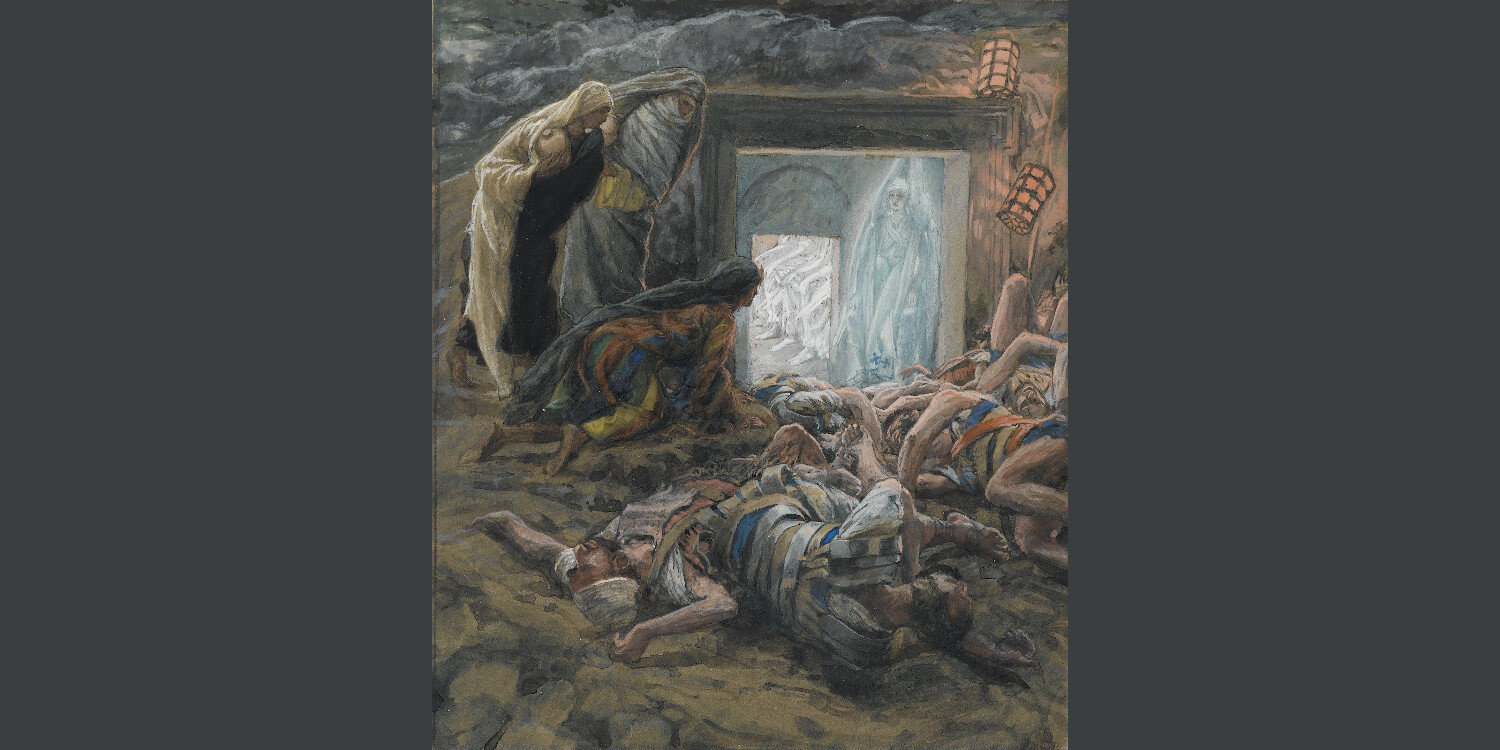

In all four of the Gospel accounts, it was Mary Magdalene who first discovered and announced the empty tomb, and in all four places the announcement sowed doubt, and even some propaganda. In the Gospel of Matthew (28:1-10), “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to the tomb … .” There they were met by an angel who instructed them, “Go quickly and tell his disciples that he has risen from the dead and behold, he is going before you to Galilee.”

Then, in Saint Matthew’s account, Jesus appeared to them on the road and said, “Do not be afraid. Go and tell my brethren to go to Galilee, and there they will see me.” Put yourself in Mary Magdalene’s shoes. She, from whom he cast out seven demons; she, who watched him die a gruesome death, is to find Peter, tell this story, and expect to be believed?

Immediately after in the Gospel of Matthew, the Roman guards went to Caiaphas the High Priest with their own story of what they witnessed at the tomb. Like the thirty pieces of silver used to bribe Judas, Caiaphas paid the guards to spread an alternate story:

“Go report to Pilate that Jesus’ disciples came and stole his body while the guards slept…’ This story has been spread among the Jews even to this day”

Apostle to the Apostles

It makes perfect sense. I, too, have seen “truth” reinvented when there is money involved. Remember that Mary Magdalene is a woman alone, with demons in her past, and she must convey her amazing account to men. So suspect is she as a source that even the early Church overlooked her witness. When Saint Paul related the Resurrection appearances to the Church at Corinth about twenty years later, he omitted Mary Magdalene entirely:

“He appeared to Cephas [the Greek name for Peter], then to the Twelve, then to more than 500 brethren at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James then to all the Apostles. Then last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared to me, for I am the least of the Apostles.”

Saint Paul lists six appearances of Jesus during the forty days between the Resurrection and the Ascension. One of those appearances “to more than 500” appears in none of the Gospel accounts. Saint Paul likely omitted the fact that it was Mary Magdalene from whom news of the Resurrection first arose, and to whom the Risen Christ first appeared, because at that time in that culture, women could not give sworn testimony.

And remember that there was another matter Mary Magdalene had to reconcile before conveying her news. It is the elephant in the upper room. She must not only tell her story to men, but to men who fled Golgotha while she remained. Among all in that room, only Mary Magdalene and the Beloved Disciple John saw Christ die. Peter, their leader, denied knowing Jesus and remained below, listening to a cock crow.

I have imagined another version of Mary Magdalene’s empty tomb report to Peter. I imagined reading it between the lines, but of course it isn’t really there. Still, it’s the version that would have made the most human sense: Mary Magdalene burst into an upper room where the Apostles hid “for fear of the Jews.” She summoned the courage to look Peter in the eye.

Mary M.: “I have good news and not-so-good news.”

Peter: “What’s the good news?”

Mary M.: “The Lord has risen and I have seen him!”

Peter: “And the not-so-good good news?”

Mary M.: “He’s on his way here and he’d like a word with you about last Friday.”

Of course, nothing like that happened. The words of Jesus to Peter about “last Friday” correct his three-time denial with a three-time commission of the risen Christ to “feed my sheep.” The Gospel message is built upon values and principles that challenge all our basest instincts for retribution and justice. The Gospel presents God’s justice, not ours.

Of the four accounts of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection Appearances, the Gospel of John conveys perhaps the most painful, beautiful, and stunning portrait of Mary Magdalene, all written between the lines:

“Standing by the Cross of Jesus were his mother, his mother’s sister [possibly Salome, mother of James and John], Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene.”

Also standing there is John, the Beloved Disciple, and Mary Magdalene becomes a witness to one of the most profound scenes of Sacred Scripture. Jesus addressed his mother from the Cross, “Woman, behold your son.” Is it a reference to himself or to the young man standing next to his mother? Is it both? Standing just feet away, the woman from whom he once cast out seven demons is fixated by what is taking place here. “Behold your Mother!” he says among his last words from the Cross, bestowing upon John — and all of us by extension — the gifts of grace and the care of his mother.

“Woman, Why Are You Weeping?”

“From that point on, John took her into his home,” and we took her into the home of our hearts. Mary Magdalene could barely have dealt with this shattering scene as her Deliverer died before her eyes when, on the morning of the first day of the week, she stood weeping outside his empty tomb. “Woman, why are you weeping?” Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI wrote of this scene from the Gospel of John in his beautifully written book, Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week (Ignatius Press, 2011):

“Now he calls her by name: ‘Mary!’ Once again she has to turn, and now she joyfully recognizes the risen Lord whom she addresses as ‘Rabboni,’ meaning ‘teacher.’ She wants to touch him, to hold him, but the Lord says to her, “Do not hold me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father” (John 20:17). This surprises us…. The earlier way of relating to the earthly Jesus is no longer possible.”

Hippolytus of Rome, a Third Century Father of the Church, called Mary Magdalene an “apostle to the Apostles.” Then in the Sixth Century, Pope Gregory the Great merged Mary Magdalene with the unnamed “sinful woman” who anointed Jesus in the Gospel of Luke (7:37), and with Mary of Bethany who anointed him in the Gospel of John (12:3). This set in motion any number of conspiracy theories and unfounded legends about Jesus and Mary Magdalene that had no basis in fact.

The revisionist history in popular books like The Da Vinci Code, and other novels by New Hampshire author Dan Brown, was contingent upon Mary Magdalene and these two other women being one and the same. The Gospel provides no evidence to support this, a fact the Church now accepts and promotes. This faithful and courageous woman at the Empty Tomb was rescued not only from her demons, but from the distortions of history.

“While up to the moment of Jesus’ death, the suffering Lord had been surrounded by nothing but mockery and cruelty, the Passion Narratives end on a conciliatory note, which leads into the burial and the Resurrection. The faithful women are there…. Gazing upon the Pierced One and suffering with him have now become a fount of purification. The transforming power of Jesus’ Passion has begun.”

+ + +

Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found

Who was Saint Dismas, the Penitent Thief, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Christians.

Who was Saint Dismas, the Penitent Thief, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Salvation.

“All who see me scoff at me. They mock me with parted lips; they wag their heads.”

During Holy Week one year, I wrote “Simon of Cyrene, the Scandal of the Cross, and Some Life Sight News.” It was about the man recruited by Roman soldiers to help carry the Cross of Christ. I have always been fascinated by Simon of Cyrene, but truth be told, I have no doubt that I would react with his same spontaneous revulsion if fate had me walking in his sandals that day past Mount Calvary.

Some BTSW readers might wish for a different version, but I cannot write that I would have heroically thrust the Cross of Christ upon my own back. Please rid yourselves of any such delusion. Like most of you, I have had to be dragged kicking and screaming into just about every grace I have ever endured. The only hero at Calvary was Christ. The only person worth following up that hill — up ANY hill — is Christ. I follow Him with the same burdens and trepidation and thorns in my side as you do. So don’t follow me. Follow Him.

This Holy Week, one of many behind these stone walls, has caused me to use a wider angle lens as I examine the events of that day on Mount Calvary as the Evangelists described them. This year, it is Dismas who stands out. Dismas is the name tradition gives to the man crucified to the right of the Lord, and upon whom is bestowed a dubious title: the “Good Thief.”

As I pondered the plight of Dismas at Calvary, my mind rolled some old footage, an instant replay of the day I was sent to prison — the day I felt the least priestly of all the days of my priesthood.

It was the mocking that was the worst. Upon my arrival at prison after trial late in 1994, I was fingerprinted, photographed, stripped naked, showered, and unceremoniously deloused. I didn’t bother worrying about what the food might be like, or whether I could ever sleep in such a place. I was worried only about being mocked, but there was no escaping it. As I was led from place to place in chains and restraints, my few belongings and bedding stuffed into a plastic trash bag dragged along behind me, I was greeted by a foot-stomping chant of prisoners prepped for my arrival: “Kill the priest! Kill the priest! Kill the priest!” It went on into the night. It was maddening.

It’s odd that I also remember being conscious, on that first day, of the plight of the two prisoners who had the misfortune of being sentenced on the same day I was. They are long gone now, sentenced back then to just a few years in prison. But I remember the walk from the courthouse in Keene, New Hampshire to a prison-bound van, being led in chains and restraints on the “perp-walk” past rolling news cameras. A microphone was shoved in my face: “Did you do it, Father? Are you guilty?”

You may have even witnessed some of that scene as the news footage was recently hauled out of mothballs for a WMUR-TV news clip about my new appeal. Quickly led toward the van back then, I tripped on the first step and started to fall, but the strong hands of two guards on my chains dragged me to my feet again. I climbed into the van, into an empty middle seat, and felt a pang of sorrow for the other two convicted criminals — one in the seat in front of me, and the other behind.

“Just my %¢$#@*& luck!” the one in front scowled as the cameras snapped a few shots through the van windows. I heard a groan from the one behind as he realized he might vicariously make the evening news. “No talking!” barked a guard as the van rolled off for the 90 minute ride to prison. I never saw those two men again, but as we were led through the prison door, the one behind me muttered something barely audible: “Be strong, Father.”

Revolutionary Outlaws

It was the last gesture of consolation I would hear for a long, long time. It was the last time I heard my priesthood referred to with anything but contempt for years to come. Still, to this very day, it is not Christ with whom I identify at Calvary, but Simon of Cyrene. As I wrote in “Simon of Cyrene and the Scandal of the Cross“:

“That man, Simon, is me . . . I have tried to be an Alter Christus, as priesthood requires, but on our shared road to Calvary, I relate far more to Simon of Cyrene. I pick up my own crosses reluctantly, with resentment at first, and I have to walk behind Christ for a long, long time before anything in me compels me to carry willingly what fate has saddled me with . . . I long ago had to settle for emulating Simon of Cyrene, compelled to bear the Cross in Christ’s shadow.”

So though we never hear from Simon of Cyrene again once his deed is done, I’m going to imagine that he remained there. He must have, really. How could he have willingly left? I’m going to imagine that he remained there and heard the exchange between Christ and the criminals crucified to His left and His right, and took comfort in what he heard. I heard Dismas in the young man who whispered “Be strong, Father.” But I heard him with the ears of Simon of Cyrene.

Like a Thief in the Night

Like the Magi I wrote of in “Upon a Midnight Not So Clear,” the name tradition gives to the Penitent Thief appears nowhere in Sacred Scripture. Dismas is named in a Fourth Century apocryphal manuscript called the “Acts of Pilate.” The text is similar to, and likely borrowed from, Saint Luke’s Gospel:

“And one of the robbers who were hanged, by name Gestas, said to him: ‘If you are the Christ, free yourself and us.’ And Dismas rebuked him, saying: ‘Do you not even fear God, who is in this condemnation? For we justly and deservedly received these things we endure, but he has done no evil.’”

What the Evangelists tell us of those crucified with Christ is limited. In Saint Matthew’s Gospel (27:38) the two men are simply “thieves.” In Saint Mark’s Gospel (15:27), they are also thieves, and all four Gospels describe their being crucified “one on the left and one on the right” of Jesus. Saint Mark also links them to Barabbas, guilty of murder and insurrection. The Gospel of Saint John does the same, but also identifies Barabbas as a robber. The Greek word used to identify the two thieves crucified with Jesus is a broader term than just “thief.” Its meaning would be more akin to “plunderer,” part of a roving band caught and given a death penalty under Roman law.

Only Saint Luke’s Gospel infers that the two thieves might have been a part of the Way of the Cross in which Saint Luke includes others: Simon of Cyrene carrying Jesus’ cross, and some women with whom Jesus spoke along the way. We are left to wonder what the two criminals witnessed, what interaction Simon of Cyrene might have had with them, and what they deduced from Simon being drafted to help carry the Cross of a scourged and vilified Christ.

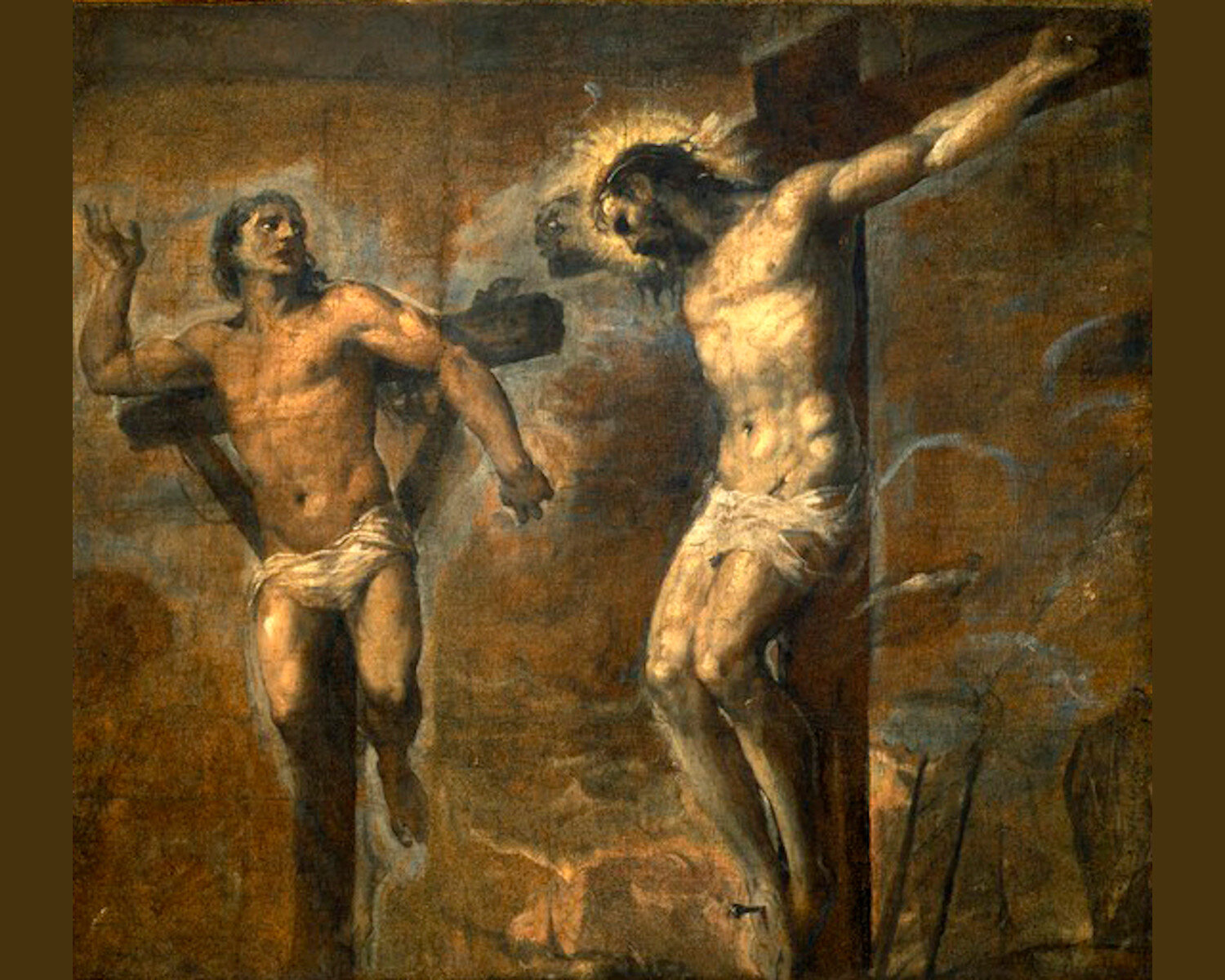

In all of the Gospel presentations of events at Golgotha, Jesus was mocked. It is likely that he was at first mocked by both men to be crucified with him as the Gospel of St. Mark describes. But Saint Luke carefully portrays the change of heart within Dismas in his own final hour. The sense is that Dismas had no quibble with the Roman justice that had befallen him. It seems no more than what he always expected if caught:

“One of the criminals who were hanged railed at him, saying, ‘Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and us!’ But the other rebuked him, saying, ‘Do you not fear God since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed justly, for we are receiving the due reward of our deeds; but this man has done nothing wrong.’ ”

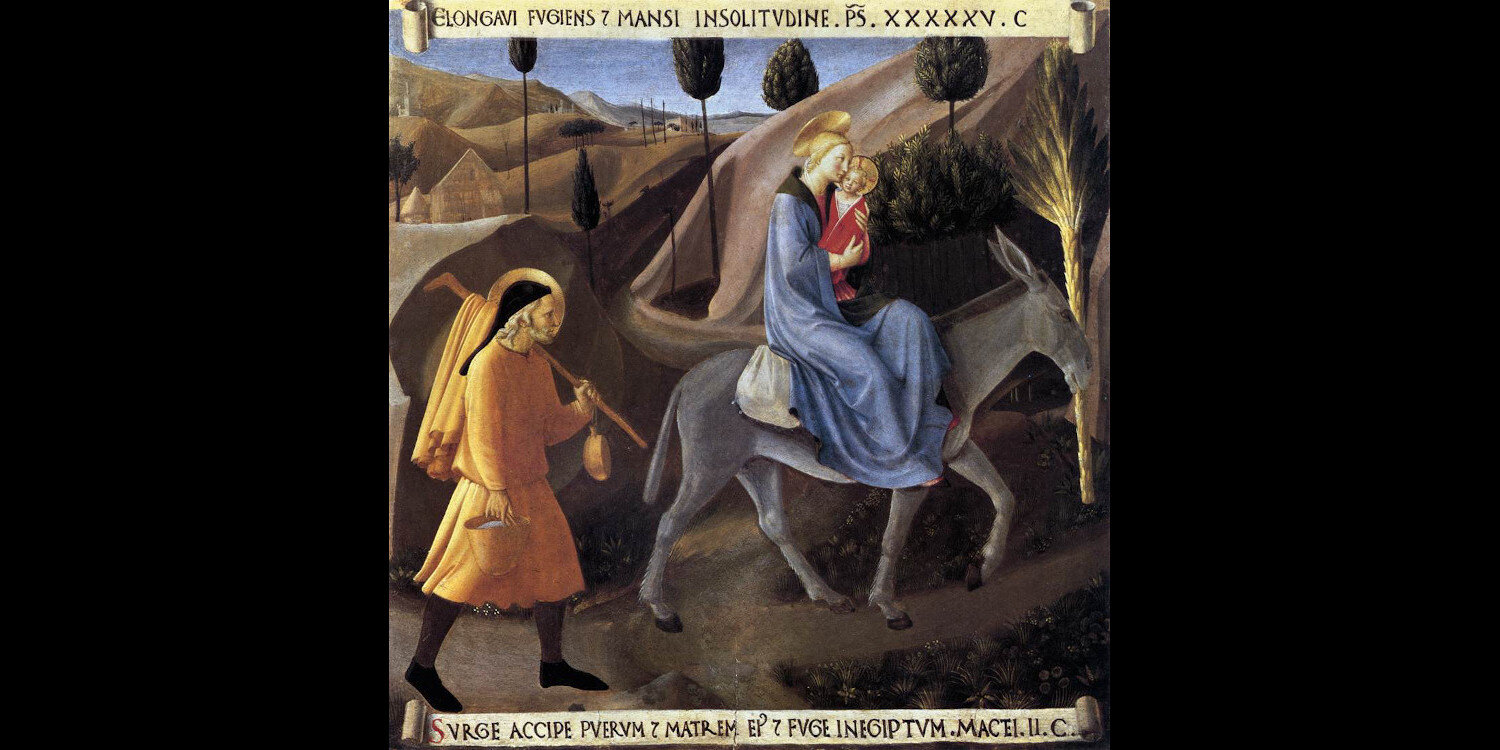

The Flight into Egypt

The name, “Dismas” comes from the Greek for either “sunset” or “death.” In an unsubstantiated legend that circulated in the Middle Ages, in a document known as the “Arabic Gospel of the Infancy,” this encounter from atop Calvary was not the first Gestas and Dismas had with Jesus. In the legend, they were a part of a band of robbers who held up the Holy Family during the Flight into Egypt after the Magi departed in Saint Matthews Gospel (Matthew 2:13-15).

This legendary encounter in the Egyptian desert is also mentioned by Saint Augustine and Saint John Chrysostom who, having heard the same legend, described Dismas as a desert nomad, guilty of many crimes including the crime of fratricide, the murder of his own brother. This particular part of the legend, as you will see below, may have great symbolic meaning for salvation history.

In the legend, Saint Joseph, warned away from Herod by an angel (Matthew 2:13-15), opted for the danger posed by brigands over the danger posed by Herod’s pursuit. Fleeing with Mary and the child into the desert toward Egypt, they were confronted by a band of robbers led by Gestas and a young Dismas. The Holy Family looked like an unlikely target having fled in a hurry, and with very few possessions. When the robbers searched them, however, they were astonished to find expensive gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh — the Gifts of the Magi. However, in the legend Dismas was deeply affected by the infant, and stopped the robbery by offering a bribe to Gestas. Upon departing, the young Dismas was reported to have said:

“0 most blessed of children, if ever a time should come when I should crave thy mercy, remember me and forget not what has passed this day.”

Paradise Found

The most fascinating part of the exchange between Jesus and Dismas from their respective crosses in Saint Luke’s Gospel is an echo of that legendary exchange in the desert 33 years earlier — or perhaps the other way around:

“‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingly power.’ And he said to him, ‘Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.’”

The word, “Paradise” used by Saint Luke is the Persian word, “Paradeisos” rarely used in Greek. It appears only three times in the New Testament. The first is that statement of Jesus to Dismas from the Cross in Luke 23:43. The second is in Saint Paul’s description of the place he was taken to momentarily in his conversion experience in Second Corinthians 12:3 — which I described in “The Conversion of Saint Paul and the Cost of Discipleship.” The third is the heavenly paradise that awaits the souls of the just in the Book of Revelation (2:7).

In the Old Testament, the word “Paradeisos” appears only in descriptions of the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2:8, and in the banishment of Cain after the murder of his brother, Abel:

“Cain left the presence of the Lord and wandered in the Land of Nod, East of Eden.”

Elsewhere, the word appears only in the prophets (Isaiah 51:3 and Ezekiel 36:35) as they foretold a messianic return one day to the blissful conditions of Eden — to the condition restored when God issues a pardon to man.

If the Genesis story of Cain being banished to wander “In the Land of Nod, East of Eden” is the symbolic beginning of our human alienation from God — the banishment from Eden marking an end to the State of Grace and Paradise Lost — then the Dismas profession of faith in Christ’s mercy is symbolic of Eden restored — Paradise Regained.

From the Cross, Jesus promised Dismas both a return to spiritual Eden and a restoration of the condition of spiritual adoption that existed before the Fall of Man. It’s easy to see why legends spread by the Church Fathers involved Dismas guilty of the crime of fratricide just as was Cain.

A portion of the cross upon which Dismas is said to have died alongside Christ is preserved at the Church of Santa Croce in Rome. It’s one of the Church’s most treasured relics. Catholic apologist, Jim Blackburn has proposed an intriguing twist on the exchange on the Cross between Christ and Saint Dismas. In “Dismissing the Dismas Case,” an article in the superb Catholic Answers Magazine Jim Blackburn reminded me that the Greek in which Saint Luke’s Gospel was written contains no punctuation. Punctuation had to be added in translation. Traditionally, we understand Christ’s statement to the man on the cross to his right to be:

“Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

The sentence has been used by some non-Catholics (and a few Catholics) to discount a Scriptural basis for Purgatory. How could Purgatory be as necessary as I described it to be in “The Holy Longing” when even a notorious criminal is given immediate admission to Paradise? Ever the insightful thinker, Jim Blackburn proposed a simple replacement of the comma giving the verse an entirely different meaning:

“Truly I say to you today, you will be with me in Paradise.”

Whatever the timeline, the essential point could not be clearer. The door to Divine Mercy was opened by the events of that day, and the man crucified to the right of the Lord, by a simple act of faith and repentance and reliance on Divine Mercy, was shown a glimpse of Paradise Regained.

The gift of Paradise Regained left the cross of Dismas on Mount Calvary. It leaves all of our crosses there. Just as Cain set in motion our wandering “In the Land of Nod, East of Eden,” Dismas was given a new view from his cross, a view beyond death, away from the East of Eden, across the Undiscovered Country, toward eternal home.

Saint Dismas, pray for us.