The Last Full Measure: Love Your Enemies

The Gospel for the 7th Sunday in Ordinary Time lays out one of the more ominous truths of Sacred Scripture: ‘The measure with which you measure will be measured out to you.’Lent is not far off, and the last Gospel readings for the Liturgy of the Church in Ordinary Time are anything but ordinary. Like so much of the Gospel, they must not be merely read and heard, but also mined, for within their depths is found freedom. No where is this more true than in one of the most challenging readings in the Gospel of Saint Luke (6:27-38) which begins with the most uncomfortable price to be paid for discipleship:

The Gospel for the 7th Sunday in Ordinary Time lays out one of the more ominous truths of Sacred Scripture: ‘The measure with which you measure will be measured out to you.’Lent is not far off, and the last Gospel readings for the Liturgy of the Church in Ordinary Time are anything but ordinary. Like so much of the Gospel, they must not be merely read and heard, but also mined, for within their depths is found freedom. No where is this more true than in one of the most challenging readings in the Gospel of Saint Luke (6:27-38) which begins with the most uncomfortable price to be paid for discipleship:

“To you who hear, I say, love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you.” (Luke 6:27)

Having been saddled with enemies I never sought, having been confronted by those who hate me, having been mistreated in ways I have never confided to you, I say, “Off with their heads!”But that is the William Wallace in me. It is not Christ in me. There are times when I have difficulty letting Him speak over the cacophony of vindictive voices I hear from this world. Sunday’s Gospel presents one of those times, but I also want to present to you two accounts of how this battle between thirst for vengeance and love of enemies has been waged.My first example is something that was done to me and something I did in response. I ask you in advance not to think less of me for it. When These Stone Walls first came into being, writer and legal researcher Ryan MacDonald compiled a Case History that he wanted posted in public view. Part III is “The Imprisonment.” It documents what happened to me in the first days after I was sent to prison in 1994 for crimes that never took place.To lose one’s freedom based on false witness is one of the worse things that can happen to a human being. To lose freedom for a lifetime renders forgiveness and love of enemies a seemingly inhuman task.The account Ryan wrote in just a few sentences has a more complex sequel. When Judge Arthur Brennan sentenced me to 67 years in prison after I three times refused a “deal” to plead guilty and serve only one year, there was a lot of local press coverage. A local newspaper chose my arrival in prison to replay a few lines from a pre-trial press release from Church officials trying to get some distance from me and minimize guilt by association. The pre-trial press release declared, “The Church has been a victim of the actions of Gordon MacRae just as these accusers have been.”Seeing that in newsprint upon my arrival in prison enraged other prisoners who knew nothing of me or this story, beyond what was published and then spread around for maximum effect. After several days of hearing rumbles of threats and scorn, I was attacked in my sleep early in the morning by three men wearing stocking caps as masks and wielding sections of broomsticks. I was beaten unconscious and sustained a permanent injury to my fourth and fifth cervical vertebrae. Because the perpetrators of the attack were unknown, I spent months in solitary confinement.After I emerged, I learned who the ringleader of the three masked assailants was. He apparently bragged about it to others and it eventually made its way to me. I never saw this person again, however, and learned that he had gotten out of prison. Ten years passed in darkness, and then in 2005 Dorothy Rabinowitz and The Wall Street Journal exploded their first investigative reporting ‘bombshell,’ “A Priest’s Story: Not All Accounts of Sex Abuse in the Catholic Church Turn Out to Be True.”Shortly after it was published, and I began to feel a sense of vindication, I obtained a job in the prison library. Part of my job at the time was to fill book requests for the fifty to sixty prisoners held in solitary confinement. Having been there once myself, I knew well that the two allowed paperback books each week were the difference between sanity and suffering in solitary confinement.DEBT OF HONORWithin weeks of starting my library job, however, I spotted a name among the stack of book request forms. It was the name of the ringleader who organized the vicious attack on me eleven years earlier, and from which I still suffered. He was back in prison, and was being held in relentless confinement in maximum security. I sat staring at his book request, reveling in this unexpected chance to get even.It was perfect. His offense against me was conspired in secret and his masked assault was anonymous. Here was my chance to repay him again and again, for week after week, in my own secret anonymity. I tore up his book request and threw it in the trash.Another week went by, a week that for him in such harsh isolation must have felt more like months with nothing but the four walls that contained him. Another stack of book requests arrived. I found his, and it was pathetic. His desperate plea for something, anything, to take his mind out beyond those relentless four walls was like a lightning bolt of revelation for me, but it was not about him. It was about me. I was stricken with the surety of truth that my using this meager power over him to deny him the one relief from his confinement available to him did not, diminish my enemy at all. It diminished only me, and I felt ashamed. My enemy spent his entire sentence in solitary confinement, but week after week from that point on I set aside my resentment and sent him the books he requested. In one week when he failed to submit a request, I submitted one on his behalf and sent him two books that I chose for him. I could have gone with Dirty Rotten Scoundrel (a title we actually have), but I took the highroad and sent two long Tom Clancy novels that would take him out of that prison cell on a mission that was honorable.This small but important setting aside of my own vindictiveness did not exactly fulfill the command of Jesus to love my enemies. But it nonetheless cost me something of myself, and it did meet the rest of His Gospel exhortation to do good to those who hate you and pray for those who mistreat you. The person who hated and mistreated me left prison without ever knowing who sent him books week after week. I do not know whether there is any hope for him, but there is hope for me.I wrote about an extreme example of this Gospel summons to pray for those who wound us in “Judas Iscariot: Who Prays for the Soul of the Betrayer?” Following that post, 1 received several letters from readers who told me that it helped them to become free of the burden of years of crushing resentment. They report finding exactly the peace that I wrote about. You simply cannot continue to hate someone for whom you are praying. The person can still be your enemy. You can still dislike that person immensely. But hate is a burden that you - and not the other person - carry to the detriment of your soul.The only caveat is that your prayer must be sincere. You cannot pray something like, “Lord please bring my enemy into the Light of Your Presence... and preferably sooner than later!” That is not a prayer. It is wishful thinking. But Jesus never said that loving your enemy and praying for those who hurt you means that your enemy is then free from being your enemy.Reconciliation is in two directions, but conversion of heart and the Gospel mandate requires only one actor. That buck stops here. Sunday’s Gospel passage ends with a mandate that should haunt our steps in life. Just remember that the conversion of heart it calls for is not usually an event. It is a process:

My enemy spent his entire sentence in solitary confinement, but week after week from that point on I set aside my resentment and sent him the books he requested. In one week when he failed to submit a request, I submitted one on his behalf and sent him two books that I chose for him. I could have gone with Dirty Rotten Scoundrel (a title we actually have), but I took the highroad and sent two long Tom Clancy novels that would take him out of that prison cell on a mission that was honorable.This small but important setting aside of my own vindictiveness did not exactly fulfill the command of Jesus to love my enemies. But it nonetheless cost me something of myself, and it did meet the rest of His Gospel exhortation to do good to those who hate you and pray for those who mistreat you. The person who hated and mistreated me left prison without ever knowing who sent him books week after week. I do not know whether there is any hope for him, but there is hope for me.I wrote about an extreme example of this Gospel summons to pray for those who wound us in “Judas Iscariot: Who Prays for the Soul of the Betrayer?” Following that post, 1 received several letters from readers who told me that it helped them to become free of the burden of years of crushing resentment. They report finding exactly the peace that I wrote about. You simply cannot continue to hate someone for whom you are praying. The person can still be your enemy. You can still dislike that person immensely. But hate is a burden that you - and not the other person - carry to the detriment of your soul.The only caveat is that your prayer must be sincere. You cannot pray something like, “Lord please bring my enemy into the Light of Your Presence... and preferably sooner than later!” That is not a prayer. It is wishful thinking. But Jesus never said that loving your enemy and praying for those who hurt you means that your enemy is then free from being your enemy.Reconciliation is in two directions, but conversion of heart and the Gospel mandate requires only one actor. That buck stops here. Sunday’s Gospel passage ends with a mandate that should haunt our steps in life. Just remember that the conversion of heart it calls for is not usually an event. It is a process:

“Stop condemning and you will not be condemned. Forgive and you will be forgiven. Give, and gifts will be given to you; a good measure, packed together, shaken down, and overflowing, will be poured into your lap. For the measure with which you measure will be measured out to you.”

THE MEASURE WITH WHICH YOU MEASURE The second account that I want to tell you about before or after you hear this Gospel proclamation is much more dramatic. Early on the morning of October 16, 2006, Manchester, NH police officers Michael Briggs and John Breckinridge responded to a call of gunshots fired at an inner city apartment which they found empty. Searching the neighborhood, they encountered a lone hooded man who was ordered to stop. The man turned and fired, and Officer Briggs was shot at close range. His partner described the scene:

The second account that I want to tell you about before or after you hear this Gospel proclamation is much more dramatic. Early on the morning of October 16, 2006, Manchester, NH police officers Michael Briggs and John Breckinridge responded to a call of gunshots fired at an inner city apartment which they found empty. Searching the neighborhood, they encountered a lone hooded man who was ordered to stop. The man turned and fired, and Officer Briggs was shot at close range. His partner described the scene:

“I watched him fall, drew my weapon, and shot four times at the fleeing man... who today resides in the Concord State Prison on death row... On the morning of October 17, Michael Briggs died for simply and bravely doing his duty as an officer.“On the days, weeks, months, and years after that fateful night I traveled on a dark, downward spiral. I hated Michael’s killer. I hated every criminal I saw. I hated the crimes they committed and the pain they caused... When the trial started in 2008, any healing that might have occurred before that was shattered as I was forced to confront Michael’s killer, relive the horrid detail of that night under the scrutiny of the court, and watch Michael’s family continue to suffer.”

Around the same time as the trial, a commission was studying whether to retain, expand, or repeal the state’s death penalty. John Breckinridge, inserting himself into the arguments, was perhaps the most informed citizen to do so for the purpose of measuring the pain and suffering such an offender caused to the community. As John described it:

“I was infuriated. I had watched [this defendant] kill my partner and now we were supposed to spend our money to feed this guy so he could read books and watch cable TV and work out. We were supposed to take the risk that some judge 20 years down the road might commute his sentence? Let’s put him to death and get it over with! I testified to keep the death penalty.”

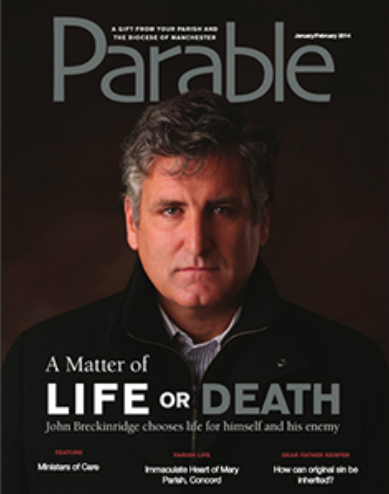

What happened within John Breckinridge over the years to follow can only best be told by John himself. He did that telling in a brief but powerful three-page article in the January-February 2014 issue of Parable Magazine entitled, “A Matter of Life and Death.”In those simple three pages, John wrote a compelling story in light of the Gospel described herein, and a stunning preparation for a meaningful Lent. I will let you read for yourself John’s path to Divine Mercy, but it is his conclusion that most drives home the point of this post:

“I am a Catholic. And today those words mean more to me than I ever thought they would, including the loss of several friends who cannot understand how a guy who has seen what I have seen could go from speaking publicly in favor of the death penalty to testifying against it. It has not been an easy journey, and ultimately I didn’t make the change. I just descended until I hit a humble enough spot in life where all I could do is ask forgiveness. He gave it unconditionally. As the receiver of that gift, who am I to rob it from someone else? Even my worst enemy.”

The Gospel that Saint Luke proclaims for the Seventh Sunday in Ordinary time does not confront the covenant of mercy in imitation of flawed humankind, but in imitation of God. In the Old Covenant - captured in the Book of Leviticus - the command of God limited such mercy to those of your own tribe:

“You shall not hate your brother in your heart, but you shall reason with your neighbor, lest you bear sin because of him. You shall not take vengeance or bear any grudge against the sons of your own people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself.” (Leviticus 19:17-18)

When Saint Luke’s Gospel uses the term “pardon” for those who offend you, it should not be understood as “forgive.” The Greek term used by the Gospel writer, ἀπολύειν, means not so much to “forgive” a wrong but to transfer its power from you to God, to wipe it out from your heart and surrender it to God.What Jesus proposes in the New Covenant, reflected most clearly in the Gospel of Luke, is a radical call to grace by expanding the term “neighbor,” earlier seen as “your own people.” The path to salvation now expands this to include God’s own people, even the stranger and the alien, even your enemy. It is not a simple task, but I propose that it is not a task for us alone. It is, as John Breckinridge has come to know, the result of our active cooperation with the grace of Divine Mercy: “the measure with which you measure will be measured out to you.”The young man who killed Officer Michael Briggs remains on death row in maximum security in the New Hampshire State Prison, but he is not so young anymore. Still, I hate what he did. Most of the prisoners I encounter here hate what he did. What John Breckinridge may not know is that in spite of what his enemy did, I send him two paperback books each week.Editor’s Note: Please share this post. You may also like these related posts from These Stone Walls:

- On the Road to Jericho: A Parable for the Year of Mercy

- Les Miserables: The Bishop and the Redemption of Jean Valjean

- Stay of Execution! Catholic Conscience and the Death Penalty

- Suffering and St. Maximilian Kolbe Behind These Stone Walls